Dodge City (1939)

Max Steiner’s Early Western Film Scores

Released in the Spring of 1939, Michael Curtiz’s Dodge City ushered in a new era for the Western, successfully combining the nation-building narrative common to previous films of this genre with the romance and heroics of the swashbuckler. It was at the forefront of a resurgence in the production of feature-length Westerns that would last until 1942, when war temporarily interrupted their revival.[1] Perceiving that audiences were weary of the epic romantic adventures and gangster films, studios turned to the historical Western to revive audience interest and offer the public a patriotic experience to bolster the national disposition toward the end of the Depression. As cultural historian Richard Slotkin observes, Westerns can tell the American story in terms of “thrilling anecdotes” and positive Westerns, like Dodge City, were a way to “affirm American values” in response to the looming crisis in Europe.

This essay considers the larger context of Dodge City as a swashbuckler-western, a combination that would re-energize the genre, overviewing its narrative and musical traits relative to its predecessors and discussing how Steiner adapted it to fit the West. Focusing specifically on a significant action scene, I will then examine how Steiner altered themes for dramatic effect and also self-borrowed for expediency if not efficacy.

A comparison of the title cards from other popular Curtiz films (like Robin Hood, 1938 and The Private Lives of Elizabeth & Essex, 1939) demonstrates similar artistic effects and the presence of similar Hollywood stars. These not only connected Dodge City to the previous costume dramas, but made it appealing as a different kind of Western. As soon as the main credits began to roll, audiences were in well-known territory.

Like the swashbuckler, Dodge City maintains the predictable clash of good vs. evil and innocence vs. corruption. Curtiz transplants these conflicts to post-Civil War frontier Kansas, maintaining the narrative arch that was also typical of the swashbuckler: Hero and heroine meet (with some initial hesitancy on the part of the heroine), they fall in love while the villains scheme around them, the threats to society increase and seem to defeat the lovers, but they prevail and are united, conquering (usually by killing) the bad elements and bringing about peace.

The plot of Dodge City centers on Wade Hatton (Errol Flynn). Originally a buffalo hunter for the railroad company, now that the railroad is finished he leads a cattle drive and wagon train, with his partner Rusty (Allan Hale), to the expanding town of Dodge City. Included with the pioneers moving west is Abbie Irving (Olivia de Haviland). Once in Dodge City Hatton witnesses the murder of several ranchers at the hand of the town tyrant, Jeff Surrett (Bruce Cabot). As the barber describes it to Hatton, the town is “Just the same as always: gambling, and drinkin’ and killin’ — mostly killin’.” When Hatton witnesses the tragic death of a young boy due to the unrestrained violence in the town, he decides to become sheriff and civilize the town while winning the love of young Abbie. Dodge City was the first of several similarly themed Westerns, many starring Flynn, and named for towns, such as Virginia City (1940) and San Antonio (1945), among others.

The parallels between Dodge City and Flynn’s most recent swashbucklers, evident in the visual and narrative aspects, are also heard in the music, including a nearly wall-to-wall prominent orchestral sound, sonic differentiation between the good and evil characters, and frequent mickey-mousing. However, Steiner also incorporates features that reflect the frontier musical aesthetic, such as melodies that sound subtly like folk songs and syncopated rhythms, emulating the lurching or plodding equestrian pace of the West. Calling on his experience with silent cinema orchestras, Steiner relied on many of the Western stereotypes or clichés found in the photoplay music of silent film to accompany the action, yet he enhances or embellishes these passages with dissonant harmonies and rapid key changes. Steiner also differentiates the tense action scenes through the use of dramatic recitative-like textures.

Steiner felt strongly that the music in motion pictures should reflect the action as closely as possible and this is exhibited in the details of his scoring, which changes dramatically depending on what is happening onscreen. His stated objective was to compose music that fit the picture “like a glove” and not establish an overall mood.[2] In her study of the music in John Ford’s Westerns, How the West Was Sung, Kathryn Kalinak calls this the “intricate interconnectedness between music and narrative action” and she notes how Steiner had a “penchant for responding to the slightest narrative provocation with music” (p. 169).

The most complex and interesting example of action music in Dodge City is heard during the climactic gunfight at the end of the film. At this point, Sheriff Hatton has arrested Surrett’s henchman, Yancy, who is responsible for all of the murders that have taken place in Dodge City. To protect Yancy from a lynch mob, Hatton takes him via train to Wichita for trial. Surrett and his associates, however, sneak on the train as it pulls out and a gunfight ensues, during which the train catches on fire. Abbie, who is also on the train for some unexplained reason, has heard the gunshots and enters in the middle of the fight. Surrett uses her as a shield to escape the burning car, locking Hatton, Rusty, and Abbie inside. They manage to escape, however, and shoot Surrett and his associates as they try to ride away.

There are two interesting facets of Steiner’s approach to this lengthy scene that I’d like to examine in detail. The first is his adaptation of Abbie’s theme to advance the action and enhance the drama, and the second is his use of pre-existing music.

Abbie’s Theme. (All transcriptions by the author based on Steiner’s sketches.)

Abbie’s theme, when first presented, is sweet, romantic, and softly orchestrated. It accompanies a flirtatious moment between Abbie and Wade Hatton. The melody is played by the strings with an arpeggiated E-flat chord in the harps and celli. In the score, Steiner notes to Friedhofer, “lots of strings – a little [woodwind]” and adds “do it anyway you want – it’s the ‘love interest’ !! awakening in the Hero!!” And he adds a pornographic drawing to make his point.

For the gunfight scene, Steiner alters the presentation of the theme, abbreviating it to just the beginning notes, notably leaving off the lyrical development in the second half. The repeated notes, now rhythmically augmented, function to intensify the action.

In this context, we hear this melody for the first time as we see Abbie sitting in the train looking out the window and again when she sees the shadow of one of the bad guys climbing on top of the train. Her reaction is punctuated by an intentionally dissonant chord (as noted by Steiner on the score: “dissonance intended”). Although Steiner indicated a sforzando in the film this chord is surprisingly quiet. Note the chords in the accompaniment that provide the rhythmic motion of the moving train.

We hear Abbie’s theme again as Surrett and his men walk by her seat on the train. She knows something is wrong and the sequentially ascending statements of this tense version of her theme heightens the suspense. With each repetition the melody becomes more dramatic, not only through the stepwise intensification, but with slight alterations in the rhythm and orchestration.

The next time we hear Abbie’s theme is when she enters the train car where the gunfight is raging. Working up to this climactic point, a short motive is reiterated ascending sequentially until it halts abruptly on an A-flat minor chord. The statement of her theme, now in the same minor key and in its lowest register yet, is very slow and dramatic with the last note extended and re-stated in an ominous triplet. Steiner reacts to this plot twist and comments in the score, “Oh nuts!!”

Now locked in the burning train car with no apparent way out, the three heroes are desperate. Hatton picks up Abbie and carries her through the fire.

As they stare horrified at the flames, Abbie’s theme is stated twice, separated by a measure of 6/8, for the reverse shot of the fire. The third time, however, Hatton spots the ax on the wall, revealing a way out of the burning car. Now Abbie’s theme is heard in a bright triumphant E major, bolstered by heroic brass.

Abbie’s entire theme is heard one last time at the very end of the film, returned to its original soft, romantic tone. The excitement is over; it has served its purpose.

While Abbie’s theme is a good vehicle for increasing tension, it would not make sense for audiences to hear it if she is not onscreen, so before she enters the car where the gunfight is raging, Steiner looked to other sources for musical inspiration. As we know, Steiner often reused his own music, likely due to time pressures and in Dodge City this occurs almost exclusively in the latter cues, when, one assumes, he was nearing a deadline.

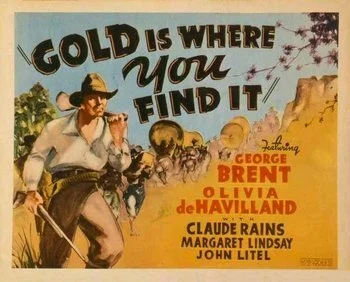

In the sequence before Abbie enters the train car, Steiner borrows three cues from his previous Western score, Gold Is Where You Find It (1938). Although Gold is more of a dramatized documentary, chronicling the tense showdown between Sacramento wheat farmers and hydraulic gold mining in 1880s California, the violence and mayhem that characterize the narrative offers musical parallels.

Just as the fire begins in the train car, Steiner adapts almost the entire opening fight scene from Gold (Reel 1, part 3). Lance Ferris, the wheat farmer’s son, is drunk in a bar and three unknown thugs pick a fight with him. Jared Whitney, the newly arrived engineer who will be working for the gold mine, steps in just as Lance draws his gun and is about to shoot. Jared grabs Lance’s arm and the two struggle as Lance’s gun goes off several times. Notice the high level of mimicking that takes place in this scene, such as when Lance throws his drink in the bad guy’s face, when he takes a punch and falls on the floor, and when he begins to shoot. These actions are all closely followed by the music. This is the scene from Gold.

In Dodge City Steiner skips over some of these measures and adapts others. With the possible exception of the falling lamp (highlighted by harp glissandi), the musical details that provided the mickey-mousing (the mimicking of the physical movement by the music) in Gold do not suit the action here. The original cue is fairly complicated, so I have isolated just a couple of key motives: listen for the disjunct chords ascending sequentially (a) and the stepwise motive that was heard when Lance was shooting (b). In Gold, this latter motive (b) is heard twice, but in Dodge City it is only stated once.

One of the more interesting adaptations in Dodge City is heard as the fire grows in the train car and the point of view changes to Yancy who is handcuffed and unable to avoid the threatening fire. The music Steiner adapted from Gold (Reel 4, Part 2) is the tragic music that accompanies the collapse of a wheat farmer’s house, killing his wife and child. It is a devastating moment and the music reflects this. The initial descending dissonant runs are followed by alternating minor seconds that repeat higher as the farmer runs to save his family.

Steiner’s reuse of this music in Dodge City signals Yancy’s unfortunate position and the urgency of unlocking his handcuffs. However, the minor seconds that communicate the wheat farmer’s anguish are cut short in Dodge City and the visual changes to an exterior shot of the burning train.

There is a brief pause as the action shifts outside to the engineer being held at gunpoint. At this point, Steiner borrows the music that accompanies a similarly tense passage in Gold (Reel 9, pt. 4) where the miners are shooting it out with the farmers as Jared runs to dynamite the dam. The music features ascending and descending runs at the beginning, accompanying Jared as he jumps off the cliff, and then a brief pause for the miners’ dialogue. As the shooting resumes and Jared gets up again, the music begins the ascending sequential repetition of a short motive until it reaches a triumphant climax when Jared reaches the top of the hill.

While this music may fit the action “like a glove” in Gold, it does not in Dodge City. The initial ascending and descending lines do not provide the mickey-mousing function as they did in Gold and the pause for the dialogue in the previous film makes little sense in this one, since there is no need for a pause. In Dodge City the camera shifts from an overall shot of Surrett and his men struggling to avoid the flames to a closer focus on Hatton and Rusty, pausing on them slightly; yet it still feels awkward. To Friedhofer’s credit, the orchestration, which was heavy with extra horns in Gold, has additional harp glissandos to highlight the flames.

Starting with the end of part 2, that is, just as Abbie enters into the railroad car, Steiner begins borrowing from cues heard earlier in the film. It struck me as rather puzzling that he didn’t do this in the previous section, and I concluded that Steiner was likely looking to draw narrative connections at the end of the film with previous passages that would provide musical interest and bring about closure. These borrowings include references to Abbie’s theme (as discussed earlier) and also a bit of the bad guys’ theme as they attempt to escape. Other music associated with the bad guys, primarily riding music, continues to dominate. The main title theme is briefly heard when Rusty is seen heroically chopping through the back of the burning car to escape.

In one instance, Steiner creates a “come sopra within a come sopra” [literally, like above within a like above] reusing music first heard during a deadly cattle stampede toward the beginning of the film and then again to accompany the death of the young boy. This harsh music is used at the end of the gunfight for dramatic effect, as Surrett and his men leap on to horses, escaping the burning train.

“As this is a come sopra within a come sopra please copy from parts to save time.”

The borrowings throughout the gunfight indicate that while Steiner considered them a short-cut to finishing the cue, he also wanted to ensure that the music fit the action and enhance the narrative. It is notable that in using the musical borrowings from Gold, Steiner was only concerned that the overall tone fit the action, overlooking the places where the music didn’t fit. In the last part, however, he sought to make narrative links with earlier parts of the movie by recalling specific motives. Ultimately, Steiner was careful about making modifications where necessary to make sure the music fit the visuals. Steiner consistently composed with this in mind, thereby developing an approach for the classic Western that was adopted by other film composers. This close interconnectedness between the music and what was happening on the screen would dominate Westerns until Jerome Moross’s groundbreaking score for The Big Country in 1958.

[1] Richard Slotkin, Western Movies: Myth, Ideology, and Genre, “Dodge City.” Audio podcast of January 8, 2009 lecture.

[2] Inter-office communication from Max Steiner to Carlyle Jones, Public Department, dated March 11, 1940. Written in response to this article: Bruno David Ussher “Composing for Films: Opportunities for Creation by Writers of Music in Hollywood” New York Times, January 28, 1940.